Jonathan E. Robins is Associate Professor of History at Michigan Tech University. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke , he discusses the story — and challenges — of palm oil:

What is the history of palm oil?

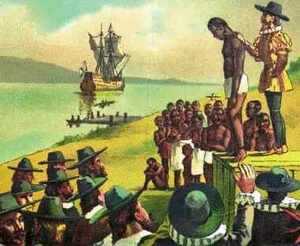

■ This product had been used for thousands of years in Africa . But the beginnings of the transatlantic slave trade in the 16th and 17th centuries brought people, food and products outside Africa. Palm oil was used to feed enslaved captives on slave ships. It was also used as a cosmetic — before they were auctioned off in America, it was applied to make the skin of enslaved people look shiny and healthier. It also played a role in the colonial scramble for Africa — palm oil was an important motivation for European empires to seize territory, trying, for instance, in Nigeria and Cameroon to secure and monopolise access to oilproducing regions. Later, it reached Southeast Asia — in the 19th century, the British began to expand their control over the Indian Ocean area. They transferred oil palm seeds and other plants they thought were economically useful across the region. The Dutch were also involved — a consignment of oil palm reached then-Dutch East Indies in 1848, taking root there.

Who were the workers growing this crop?

■ Initially, in Southeast Asia, there was little local interest in palm oil because coconut was a well-established industry. In the 20 th century, when prices for all commodities, but particularly edible oils, began to skyrocket around WWI , high prices for oil drew Europebased companies to invest in oil palm plantations in the region. They copied the established business model for rubber, where colonial governments took land from local people and leased it to European companies — they then imported workers from India, Java or China, often under indenture contracts. The wages these plantations paid were simply not high enough to attract locals — they thus relied on recruiting labour from places with fewer opportunities, limited access to land, overpopulation and often, famine conditions which compelled people to seek overseas work, even at low wages.

How did palm oil then get involved in post WWII development plans?

■ In the 1950s-60s, the World Bank and former colonial powers, like the British and French, began looking for projects that could create jobs in ex-colonies and increase supplies to address what many believed was an impending global food crisis. Being a labour-intensive crop, the palm oil industry provided a lot of employment while creating a material useful for food and other products. Eventually, that became part of the development narrative of post-colonial economies like Malaysia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, etc. Instead of rejecting colonial crops, independent governments embraced them as a source of revenue that could be channelled into other development projects.

What is the history of palm oil, fats and ‘an industrial diet’?

■ This story begins in the 19th century when a series of discoveries in chemistry revealed new ways of manipulating natural fats from plant and animalbased oils. Manufacturers were seeking to reduce costs — one way was by making raw materials interchangeable. So, they used chemistry to modify fats from different plant and animal sources. The cheapest products using palm oil first were candles and soap — it then found itself in food. In the late 19 th century, new products, like margarine, cooking and frying fats, began to be developed. They were simply sold as new ‘industrial’ fats — one week, they might be made with hydrogenated cottonseed oil, another week, with palm oil. For manufacturers, these fats being substituted so easily was very appealing.

Palm oil became such a significant part of this system because the plant is an extremely efficient producer of fats and has both unsaturated liquid components and saturated fats, which makes it applicable across industries.

Can you tell us about its presence in modern soap?

■ West Africans made soap using palm oil centuries ago — in the 18th century, European travellers there described such locally-made soaps. Europeans began using it first as a colouring agent. Raw, unrefined palm oil has a striking red or orange colour — when fresh, it also has a very interesting scent. This combination made palm oil an attractive ingredient for early soap manufacturers.

In the 19 th century, as Britain moved to abolish the slave trade, British merchants and shipping companies began exporting more and more palm oil to make up for that commercial loss. Its price fell and as it became cheaper, soap makers began to use it as their main ingredient.

How did it make its way into weaponry?

■ The main connection is through a product that all fats contain called glycerine — for years, this had been discarded as a waste product but then, chemists discovered it could be used to make, among other things, explosives. Nitroglycerin was the first major explosive based on this.

A series of other applications derive from this use of palm oil — napalm was initially developed using palmitic acids drawn from it, a thickened sort of gasoline product that burns. Later manufacturing shifted to other materials — yet, palm oil was important enough to give this weapon its name ‘napalm’.

What are palm oil’s environmental impacts?

■ The Southeast Asian industry in particular grew at the expense of destroying primary forest which was first targeted by colonial plantations. This continued post-independence. Deforestation is also of great concern in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. But other impacts include water pollution — factories extracting palm oil use enormous amounts of water. Until the 1980s, most byproducts of this process were just dumped into local waterways, causing pollution. This is still a problem in many ‘frontier’ areas where oil palm is a newly developed industry. The mills started there often don’t have the equipment and infrastructure to safely process waste — hence, deforestation combined with water pollution produces very negative impacts.

Palm oil employs millions though — are there sustainable ways forward?

■ It’s a challenge because palm oil is often invisible in the products we consume — rarely can we see its colour or taste its flavour. Those components have been intentionally removed from most palm oil added to consumer products. I’d suggest people think about palm oil with curiosity and concern. It is a very important food product, it sustains billions and converting it now, for instance, into biofuel is a concern for some who worry that the rush to embrace biodiesel and ‘green fuels’ will not only accelerate deforestation but also increase food prices.

These issues are one reason I use a commodity approach in my research — this allows us to grasp onto physical objects that connect us to different regions, organisations, governments, corporations and real people who produce and consume these things. Commodities help us avoid abstractions — they ground our understanding of global challenges, environmental to economic, in a way where we can see their origins in history and hopefully use that to address our own world.

What is the history of palm oil?

■ This product had been used for thousands of years in Africa . But the beginnings of the transatlantic slave trade in the 16th and 17th centuries brought people, food and products outside Africa. Palm oil was used to feed enslaved captives on slave ships. It was also used as a cosmetic — before they were auctioned off in America, it was applied to make the skin of enslaved people look shiny and healthier. It also played a role in the colonial scramble for Africa — palm oil was an important motivation for European empires to seize territory, trying, for instance, in Nigeria and Cameroon to secure and monopolise access to oilproducing regions. Later, it reached Southeast Asia — in the 19th century, the British began to expand their control over the Indian Ocean area. They transferred oil palm seeds and other plants they thought were economically useful across the region. The Dutch were also involved — a consignment of oil palm reached then-Dutch East Indies in 1848, taking root there.

Who were the workers growing this crop?

■ Initially, in Southeast Asia, there was little local interest in palm oil because coconut was a well-established industry. In the 20 th century, when prices for all commodities, but particularly edible oils, began to skyrocket around WWI , high prices for oil drew Europebased companies to invest in oil palm plantations in the region. They copied the established business model for rubber, where colonial governments took land from local people and leased it to European companies — they then imported workers from India, Java or China, often under indenture contracts. The wages these plantations paid were simply not high enough to attract locals — they thus relied on recruiting labour from places with fewer opportunities, limited access to land, overpopulation and often, famine conditions which compelled people to seek overseas work, even at low wages.

How did palm oil then get involved in post WWII development plans?

■ In the 1950s-60s, the World Bank and former colonial powers, like the British and French, began looking for projects that could create jobs in ex-colonies and increase supplies to address what many believed was an impending global food crisis. Being a labour-intensive crop, the palm oil industry provided a lot of employment while creating a material useful for food and other products. Eventually, that became part of the development narrative of post-colonial economies like Malaysia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, etc. Instead of rejecting colonial crops, independent governments embraced them as a source of revenue that could be channelled into other development projects.

What is the history of palm oil, fats and ‘an industrial diet’?

■ This story begins in the 19th century when a series of discoveries in chemistry revealed new ways of manipulating natural fats from plant and animalbased oils. Manufacturers were seeking to reduce costs — one way was by making raw materials interchangeable. So, they used chemistry to modify fats from different plant and animal sources. The cheapest products using palm oil first were candles and soap — it then found itself in food. In the late 19 th century, new products, like margarine, cooking and frying fats, began to be developed. They were simply sold as new ‘industrial’ fats — one week, they might be made with hydrogenated cottonseed oil, another week, with palm oil. For manufacturers, these fats being substituted so easily was very appealing.

Palm oil became such a significant part of this system because the plant is an extremely efficient producer of fats and has both unsaturated liquid components and saturated fats, which makes it applicable across industries.

Can you tell us about its presence in modern soap?

■ West Africans made soap using palm oil centuries ago — in the 18th century, European travellers there described such locally-made soaps. Europeans began using it first as a colouring agent. Raw, unrefined palm oil has a striking red or orange colour — when fresh, it also has a very interesting scent. This combination made palm oil an attractive ingredient for early soap manufacturers.

In the 19 th century, as Britain moved to abolish the slave trade, British merchants and shipping companies began exporting more and more palm oil to make up for that commercial loss. Its price fell and as it became cheaper, soap makers began to use it as their main ingredient.

How did it make its way into weaponry?

■ The main connection is through a product that all fats contain called glycerine — for years, this had been discarded as a waste product but then, chemists discovered it could be used to make, among other things, explosives. Nitroglycerin was the first major explosive based on this.

A series of other applications derive from this use of palm oil — napalm was initially developed using palmitic acids drawn from it, a thickened sort of gasoline product that burns. Later manufacturing shifted to other materials — yet, palm oil was important enough to give this weapon its name ‘napalm’.

What are palm oil’s environmental impacts?

■ The Southeast Asian industry in particular grew at the expense of destroying primary forest which was first targeted by colonial plantations. This continued post-independence. Deforestation is also of great concern in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. But other impacts include water pollution — factories extracting palm oil use enormous amounts of water. Until the 1980s, most byproducts of this process were just dumped into local waterways, causing pollution. This is still a problem in many ‘frontier’ areas where oil palm is a newly developed industry. The mills started there often don’t have the equipment and infrastructure to safely process waste — hence, deforestation combined with water pollution produces very negative impacts.

Palm oil employs millions though — are there sustainable ways forward?

■ It’s a challenge because palm oil is often invisible in the products we consume — rarely can we see its colour or taste its flavour. Those components have been intentionally removed from most palm oil added to consumer products. I’d suggest people think about palm oil with curiosity and concern. It is a very important food product, it sustains billions and converting it now, for instance, into biofuel is a concern for some who worry that the rush to embrace biodiesel and ‘green fuels’ will not only accelerate deforestation but also increase food prices.

These issues are one reason I use a commodity approach in my research — this allows us to grasp onto physical objects that connect us to different regions, organisations, governments, corporations and real people who produce and consume these things. Commodities help us avoid abstractions — they ground our understanding of global challenges, environmental to economic, in a way where we can see their origins in history and hopefully use that to address our own world.

You may also like

'I'm a car expert - this popular hatchback is the perfect future classic'

Saiyaara Box Office Collection Day 2: Ahaan Panday, Aneet Padda's Film Is Unstoppable, Mints ₹24 Crore On Saturday

Mumbai Anticipated To Face Heavy Rainfall For Next 48 Hours; IMD Issues Alert

'Being still is a challenge': Shubhanshu Shukla shares video of floating in space - Watch

Brits offered £3,750 to switchover to EVs but experts warn of huge catch